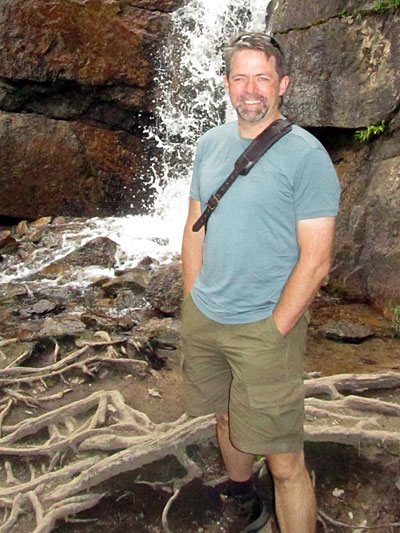

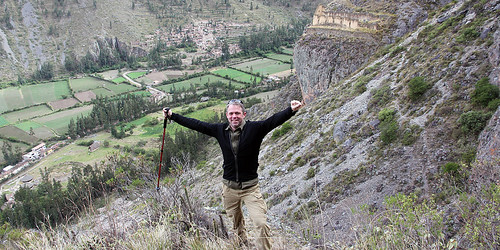

I’ve been home now for 72 hours. Three days ago, our plane from Lima landed in Portland, and ever since, I’ve been trying to adjust.

In a way, it’s good to be home. The trees are gorgeous this fall. I’ve enjoyed eating at some of my favorite haunts, and it’s been good to be back to the gym and back to Spanish lessons. At the same time, though, I miss Peru. I don’t want to be here — I want to be there. (Although perhaps while transplanting some of my favorite things about the Pacific Northwest…)

There’s still lots to write about my six-week trip. I have many photos and stories to share. Today, though, I want to talk about one small part of Peru that I miss most: the animals. One of my favorite differences between Peru and the United States is the way that people treat animals. (And children, but that’s another story.)

I’m an animal lover. I have a (near-dormant) blog about animal intelligence in which I’ve written some about my respect for the emotional and intellectual lives of the creatures around us. But one thing I regret about animals in the U.S. is how removed they are from our lives.

Yes, many people keep animals as pets. (I have five cats!) But often these pets are indoor-only, and when they go outside, they do so on a leash. Our animals don’t lead very natural lives, even on farms. Instead, it’s like we’ve created a pocket universe where they’re insulated from us and we’re insulated from them. I’m not sure why this is the case.

In Peru, however, it’s different — at least outside of Lima. In Peru (and in Bolivia), animals are everywhere. Cats and dogs roam the streets, as do llamas and burros and more. In the countryside, the livestock is unfenced. It’s herded or allowed to roam free. The net effect is that people and animals have integrated each other into their lives.

This means you might stay in a hotel where the cats wander freely from room-to-room, including the lobby and the kitchen. Or you might encounter llamas wandering in the streets. And everywhere you go, you find dogs of all shapes and sizes. These animals all interact with each other, and with the people, and with the traffic. It’s like a parallel world.

I think the most prominent example of this is the way dogs roam the streets of Cusco (and other cities in the Sacred Valley). Dogs run free in Cusco, without leashes or collars. They respect the people and the traffic, and the people and traffic respect them. Everyone — man and beast — follows certain rules, and everyone is happy. It’s fun to see a dog (or a group of dogs) trotting along on some sort of canine agenda. It’s also fun to see the animals sitting or sleeping on the sidewalks and steps around town.

I love seeing a society that allows the animals to create their own network of social interactions, one that lets them eat, sleep, and go about their business. To me, this is vastly preferable to the way we treat animals in the U.S.

My wife and I have always allowed our cats to go inside and outside at will, which has drawn criticism from some friends and readers. We’re unfazed. The cats are clearly happier when they can roam freely, just as you would be too. Visiting Peru has only reinforced my belief that it’s healthiest for the animal live an unfettered life (or at least as unfettered as possible).

I’ll leave you with a few more photos of the animals I met in Peru. And then I’ll walk home along empty streets — streets that could contain cats and dogs and horses and burros and lambs and llamas…but don’t.