I’ve been reading a lot of old comic books lately. Since I love comics, this probably doesn’t sound unusual. But it is. I mean I’ve been reading actual comics (instead of compilations) from the 1950s and 1960s.

I find these books entertaining, even though their stories are often dull and repetitive. (The DC comics of the era are just plain bad most of the time.) I’m fascinated by the window to the past these comics provide, by the glimpses they give of culture and values that have faded to memory.

For example, I think we take it for granted how far the role of women has come in U.S. society. Sure, there’s more work to be done, but when you see how women were portrayed in comics fifty years ago, it’s like a whole other world.

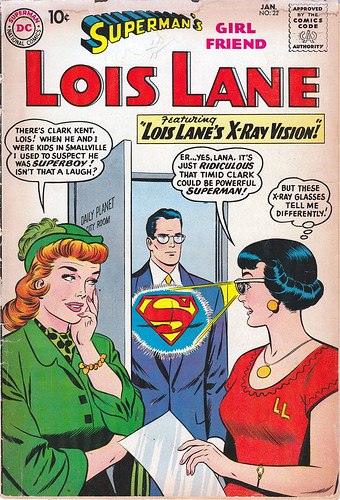

My favorite example of this is the Lois Lane comic series, the full title of which is Superman’s Girl Friend Lois Lane. Every issue contains three stories, and every story features Lois pining for Superman. (She’s usually trying to prove that Clark Kent is Superman in these stories, too.) And although Lois is portrayed as a strong “girl” for her era, she still needs Superman to save her over and over again.

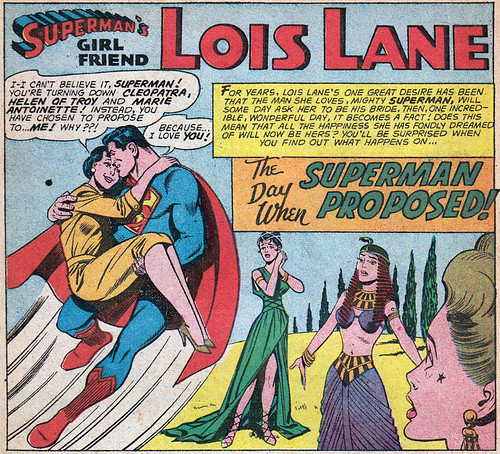

Lois Lane comics are filled with “imaginary stories”, stories that the editors claim are “what if” stories. They’re not part of the official Superman storyline, but imaginary tales about what could happen — if Lois and Superman married, for instance:

These are nice because they give the comic a change of pace. And, presumably, they satisfy the female audience’s taste for romance, though I’m dying to know the demographics of the Lois Lane readership during the early 1960s. Did women really buy these? It’s hard to believe now, but comics regularly sold hundreds of thousands of copies, and the most popular would sell over a million copies per month. Surely some women read this. But how many?

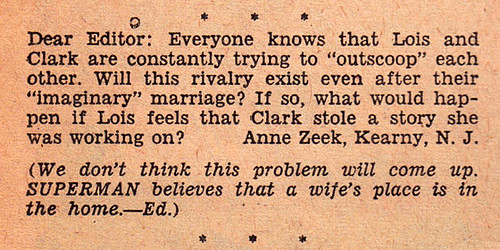

If the magazine’s letter column is any indication, plenty of women read Lois Lane (though most letters are from men). Here, for example, Anne Zeek of Kearny, New Jersey, writes to ask how Lois and Clark would handle working in the same workplace:

Dig that answer: “Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home.” Mind boggling! Can you even imagine a magazine printing something like that nowadays? Yet, fifty years ago, this was the prevailing attitude. (This letter is from the January 1961 issue of Lois Lane.)

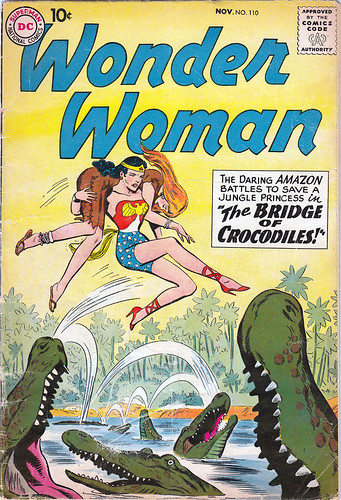

For a long time, the only bastion of strong womanhood in comics came from Wonder Woman, who starred in adventures like this (from November 1959):

Even Wonder Woman wasn’t immune to sexism, though. She palled around with Steve Trevor, “ace military intelligence pilot”, who often was depicted as stronger than she was. (Though, to be fair, most of the time the comic really did feature role reversals: Wonder Woman was saving Steve Trevor from danger.) The sad part about Wonder Woman is that after creator William Moulton Marston left the book, its writing and art sunk to the bottom of the barrel — worse even than Batman (which was dreadful at the time).

Marston was the psychologist and feminist theorist who created Wonder Woman. But even his noble aims seem patriarchal today:

Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, and power. Not wanting to be girls, they don’t want to be tender, submissive, peace-loving as good women are. Women’s strong qualities have become despised because of their weakness. The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.

Do women have stronger roles in comics today? I don’t know, to be honest. I rarely read modern comics, and almost never read modern superhero comics. I do know that when I was a boy in the 1980s, there were some strong female characters. And I can’t imagine any editor in the 1980s writing that Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home.