For the past four (almost five) months, I’ve spent most of my work hours writing an ebook. At first the book was about how to “master your money”. Then it became a treatise on financial independence. That morphed into a grander project about how to achieve financial and personal independence (and is the source of my year-long series of articles here at More Than Money). In the end, in its fourth iteration, the book turned into a manual on how to be the Chief Financial Officer of your own life.

I’m good at writing short pieces. I’ve been creating bite-sized blog posts of 500 or 1000 or 2000 words for years now, often on a daily schedule. But I’m less good at molding larger pieces of writing. I finished the first draft of my ebook on Wednesday afternoon, and it weighed in at 96 pages and just over 40,000 words. But getting to that final product felt like pulling my own teeth.

Part of the problem is I’m not good at balance. Try as I might (and I do try), I can’t figure out how to juggle all of the things I want to do in life. How does one learn guitar, study Spanish, go to the gym, cook healthy food, write weekly articles about money, all while writing a book? (Not to mention other miscellaneous tasks!) It’s tough. At least for me.

Eventually, I simply had to pull the plug on everything else, which is what I did when writing Your Money: The Missing Manual. At the end of January, frustrated because I couldn’t seem to finish the ebook, I stopped going to the gym, stopped practicing guitar, stopped studying Spanish. I got up every morning and wrote for eight or ten hours. The method worked, but I didn’t enjoy it.

Perhaps you’ll notice that this issue seems similar to others I’ve had in the past. Very similar.

To me, this “all or nothing” state of mind reminds me of how I got into (and out of) debt. It reminds me of how I gained (and lost) weight. And it reminds me of how I swore off alcohol for the month of January. For me, moderation is difficult. It’s tough to find balance.

As part of my ebook project, I’ve been conducting short audio interviews with some of my favorite folks. I interviewed Adam Baker about debt reduction, for example, Jean Chatzky about money rules, and Liz Weston about credit. In one interview, I talked to Gretchen Rubin about the relationship between money and happiness. During that conversation, we discussed the book she’s writing now, which is about habits.

Rubin says that not everyone is the same.

At one extreme, there are Abstainers. Abstainers tend to have an “all or nothing” approach to life. In order to reduce their alcohol consumption, they stop drinking. To refrain from eating cookies, they can’t have cookies in the house. Abstainers have trouble stopping something once they’ve started — but they’re not tempted by the things they’ve decided are off limits.

At the other extreme are Moderators. Moderators do better without absolutes and strict rules. Instead of swearing off cookies completely, they have one cookie on two or three nights per week. (Me? I’d eat the whole damn package!) They don’t need to go dry for a month to drink less — they simply drink less. Moderators enjoy an occasional indulgence and find that it actually strengthens their resolve instead of weakening it.

Here’s a short bit from my recent interview with Rubin in which she describes the difference between the two personality types.

Gretchen Rubin

For some people, it’s much easier to give something up all together than it is to indulge a little bit. And it’s very important to know this, because both sides try to convince each other. And Moderators – those are the people who can have a little bit – will often say things like, “You shouldn’t be so rigid with yourself. If you deny yourself everything you’ll fall off the wagon. It’s not healthy to always say no to yourself.”But the thing is, for an Abstainer, it’s easier never to have French fries. It’s easier to never have sugar. It’s easier to say none that can manage it a little bit.

This is a good test for whether you’re an Abstainer or Moderator: Let’s say that I handed you – and here, J.D., I’ll ask you too – let’s say I handed you a bar of delicious chocolate and I said, “Hey, J.D., eat a square of that chocolate.” So you eat a square. And then I’m like, “Okay, hey, just put the rest of it in the drawer of your desk.”

For the rest of the day, would you be like, “Oh, my gosh. When am I gonna eat the rest of that chocolate bar?”

Or would you be like, “Oh, I had a little bit of something sweet. I don’t want anymore. I’ll have another square tomorrow.”

J.D. Roth

No.Gretchen Rubin

I would be haunted by the chocolate bar.J.D. Roth

Yeah, me too.

Gretchen and I are Abstainers. This quality manifests itself in all aspects of my life, from work to food to money to love. It’s not necessarily a bad thing — but it is a thing. I need to be aware of this, and I need to know how to work with it to my advantage.

And, perhaps, I need to find ways to moderate this tendency. I don’t enjoy those times in my life during which I have to flip a switch and be “all or nothing” about something. I like it better when I can pretend that I’m a Moderator by drafting schedules, by deciding to develop habits and routines.

After I submitted my ebook manuscript to my editor on Wednesday, the first thing I did was sit down and draw up a schedule. Spanish in the morning! Followed by guitar practice! Then email and blog posts for Get Rich Slowly and More Than Money! Then the gym! Then more work in the afternoon!

I love the schedule. I love looking at it and imagining this ideal life where I adhere to a regular routine as if it were nothing. I know it would be good for me. But I also know that I don’t work that way. This sort of balance seems impossible to achieve. It’s a pipe dream.

Still, I’m going to try.

Right now, however, I’m going to take a long, hot bath while reading a comic book. In fact, maybe that’s what I’ll do all day…

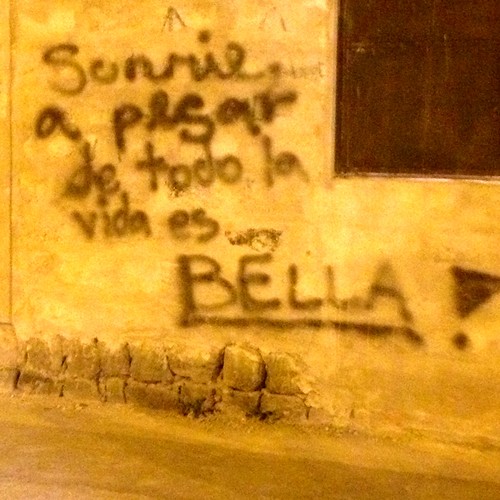

Note: Photo by Kathleen Franklin.