I’ve been reading a lot of old comic books lately. Since I love comics, this probably doesn’t sound unusual. But it is. I mean I’ve been reading actual comics (instead of compilations) from the 1950s and 1960s.

I find these books entertaining, even though their stories are often dull and repetitive. (The DC comics of the era are just plain bad most of the time.) I’m fascinated by the window to the past these comics provide, by the glimpses they give of culture and values that have faded to memory.

For example, I think we take it for granted how far the role of women has come in U.S. society. Sure, there’s more work to be done, but when you see how women were portrayed in comics fifty years ago, it’s like a whole other world.

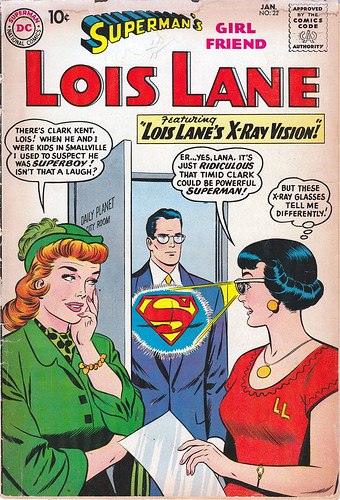

My favorite example of this is the Lois Lane comic series, the full title of which is Superman’s Girl Friend Lois Lane. Every issue contains three stories, and every story features Lois pining for Superman. (She’s usually trying to prove that Clark Kent is Superman in these stories, too.) And although Lois is portrayed as a strong “girl” for her era, she still needs Superman to save her over and over again.

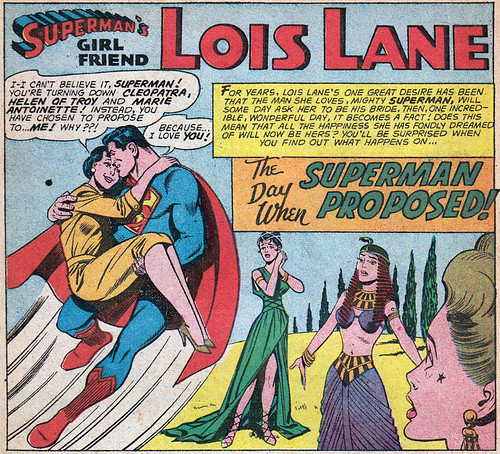

Lois Lane comics are filled with “imaginary stories”, stories that the editors claim are “what if” stories. They’re not part of the official Superman storyline, but imaginary tales about what could happen — if Lois and Superman married, for instance:

These are nice because they give the comic a change of pace. And, presumably, they satisfy the female audience’s taste for romance, though I’m dying to know the demographics of the Lois Lane readership during the early 1960s. Did women really buy these? It’s hard to believe now, but comics regularly sold hundreds of thousands of copies, and the most popular would sell over a million copies per month. Surely some women read this. But how many?

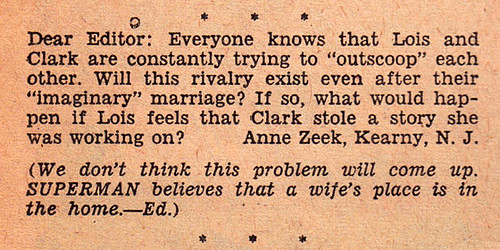

If the magazine’s letter column is any indication, plenty of women read Lois Lane (though most letters are from men). Here, for example, Anne Zeek of Kearny, New Jersey, writes to ask how Lois and Clark would handle working in the same workplace:

Dig that answer: “Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home.” Mind boggling! Can you even imagine a magazine printing something like that nowadays? Yet, fifty years ago, this was the prevailing attitude. (This letter is from the January 1961 issue of Lois Lane.)

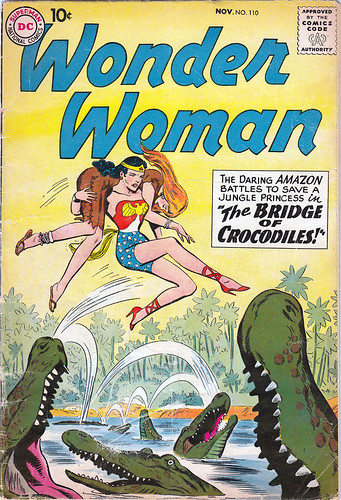

For a long time, the only bastion of strong womanhood in comics came from Wonder Woman, who starred in adventures like this (from November 1959):

Even Wonder Woman wasn’t immune to sexism, though. She palled around with Steve Trevor, “ace military intelligence pilot”, who often was depicted as stronger than she was. (Though, to be fair, most of the time the comic really did feature role reversals: Wonder Woman was saving Steve Trevor from danger.) The sad part about Wonder Woman is that after creator William Moulton Marston left the book, its writing and art sunk to the bottom of the barrel — worse even than Batman (which was dreadful at the time).

Marston was the psychologist and feminist theorist who created Wonder Woman. But even his noble aims seem patriarchal today:

Not even girls want to be girls so long as our feminine archetype lacks force, strength, and power. Not wanting to be girls, they don’t want to be tender, submissive, peace-loving as good women are. Women’s strong qualities have become despised because of their weakness. The obvious remedy is to create a feminine character with all the strength of Superman plus all the allure of a good and beautiful woman.

Do women have stronger roles in comics today? I don’t know, to be honest. I rarely read modern comics, and almost never read modern superhero comics. I do know that when I was a boy in the 1980s, there were some strong female characters. And I can’t imagine any editor in the 1980s writing that Superman believes that a wife’s place is in the home.

Hahaha, that would be a huge scandal if printed today! Someone would have to publicly apologize for a statement like that. ;)

You probably know a lot of this stuff already, but here goes:

– The main reason comics – especially the Superman comics – of the 50s and 60s were so repetitive is that there was an editorial belief that comics’ readership turned over every 3-5 years, so they could redo a story they’d done just a few years before and sell it to a new set of customers, who wouldn’t remember the last time they’d done it.

– Among DC editorial, Julie Schwartz had higher standards than this, so his books tended to be less repetitive in this way. This is a big part of why, for example, the “New Look” Batman titles of the 60s are fondly remembered – Schwartz became the editor, brought in better writers and artists, and let them do new stuff. While it can be argued whether it was actually better than what had gone before, it was certainly different, and fans appreciated that.

– The Legion of Super-Heroes in Adventure Comics was one of the Superman family of titles, and definitely had this sort of repetitiveness. I’ve read interviews with Jim Shooter (who started writing the book – famously at the age of 14 – in the mid-60s) talking about the editor handing down new repeat stories (“revolt of the girl Legionnaires”, “revolt of the Super-Pets”, “Legion of Super-Babies”, etc.) and how he dodged some of those assignments, and tried to come up with novel new ways of doing the ones he couldn’t escape.

– Hawkgirl was a relatively strong female character from around the period you’re discussing. She wasn’t very high profile because Hawkman wasn’t a strong seller. Certainly at the beginning she was portrayed as Hawkman’s equal. I haven’t read deeply into the series (just the first Archive collection). Not surprisingly, though, I think Hawkman was edited by Schwartz.

I don’t really know what the gender make-up of comics readers in the 60s was, either. My belief is that there were more female readers (certainly there were a lot more published letters from female readers as late as the late 70s), but “a lot more” could still only mean “10% of readers” compared to what we have today (where I would not be surprised if less than 1 in 100 readers of superhero comics were female).

One of the more interesting books I’ve read is the 10 Cent Plague, which touched on the demographics both of the readers – and of the people who organized public burnings of the comics.

Fascinating book. The idea of book-burnings held in the U.S., post-WWII, chills me to the core.

I grew up reading Marvel comics in the ’60’s so my expectations were a little different. Once around 1967 or so someone gave me a big box of DC comics from around 1955-1961, and I couldn’t finish them they were so awful. Completely turned me off DC comics, which all the kids in my social circle called Dull Comics, because they were. So. Dull.

Do women have stronger roles in comics today?

I don’t know either, but two graphic novels come to my mind: Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Rutu Modan’s Exit Wounds. I’d recommend both. (Of course the portrayal of women in both is strongly influenced by the fact that both authors are women.)

Persepolis is awesome!

And if you ever start watching Mad Men I fully expect you to post something similar!