In my spare time — what little there is of it — I’ve been continuing my research into the nature of fear and how that relates to success and achievement. Why does fear hold some people back yet serve as a motivator for others? As part of this, I’ve been re-reading all of Malcolm Gladwell. It’s entertaining and instructive.

How to Achieve Success

In Outliers, for instance, Gladwell explores the factors allow some people to achieve runaway success. How did Bill Gates become Bill Gates? How did The Beatles become The Beatles? And why do some people who seem to have innate talent never reach their full potential?

In Outliers, for instance, Gladwell explores the factors allow some people to achieve runaway success. How did Bill Gates become Bill Gates? How did The Beatles become The Beatles? And why do some people who seem to have innate talent never reach their full potential?

Gladwell’s hypothesis is that there are two factors necessary for success: environment and effort.

Success cannot be achieved without great personal effort. Gladwell popularized the notion (though he did not invent it) that to truly become proficient at something, to master it, you need to spend roughly 10,000 hours acquiring that skill. Bill Gates, for instance, spent about 10,000 hours learning to program. The best violinists spend about 10,000 hours practicing their instrument. And so on.

It’s nearly impossible to become successful without putting in a lot of work.

But effort alone isn’t enough. Gladwell argues that Outliers — his term for folks who achieve astounding success — come from environments that encourage and foster their talents and abilities. It’s not enough that Bill Gates was interested in computers. He had to be born into a community that gave him a chance to spend 10,000 hours programming, an environment that provided tons of opportunities to put his skills to work.

Success is the Sum of Environment Plus Effort

Warren Buffett, perhaps the world’s greatest investor, has spoken many times about what he calls “the ovarian lottery”. “You’re going to get one ball out of there, and that is the most important thing that’s ever going to happen in your life,” he once told a group of students at the University of Florida.

In his philanthropic pledge [PDF], Buffett writes:

My wealth has come from a combination of living in America, some lucky genes, and compound interest. Both my children and I won what I call the ovarian lottery. (For starters, the odds against my 1930 birth taking place in the U.S. were at least 30 to 1. My being male and white also removed huge obstacles that a majority of Americans then faced.)

My luck was accentuated by my living in a market system that sometimes produces distorted results, though overall it serves our country well. I’ve worked in an economy that rewards someone who saves the lives of others on a battlefield with a medal, rewards a great teacher with thank-you notes from parents, but rewards those who can detect the mispricing of securities with sums reaching into the billions. In short, fate’s distribution of long straws is wildly capricious.

There’s no question that Buffett worked damn hard to develop his business acumen. But he’s the first to admit that he was lucky to have been born in a time and a place that rewarded his passion.

I feel the same way about my own success. Yes, I’ve worked hard. I’ve spent far more than 10,000 hours blogging about life and money. But I’ve also been lucky, and in any number of ways. How strange is it that I came along at just the right time with just the right skills? I was a computer-geek psychology major who loved to write and was deep in debt. From these four factors, I was able to build Get Rich Slowly into something far more than I expected.

Again, success is the sum of environment plus effort.

Helping Others Succeed

It’s oft been said that “success is what happens when opportunity meets preparation”. That’s essentially the entire lesson of Gladwell’s Outliers. At the end of the book, he writes:

Everything we have learned in Outliers says that success follows a predictable course. It is not the brightest who succeed…Nor is success simply the sum of the decisions and efforts we make on our own behalf. It is, rather, a gift. Outliers are those who have been given opportunities — and who have had the strength and presence of mind to seize them.

This, too, is the core lesson of Luck is No Accident, a great book about making the most of unplanned events.

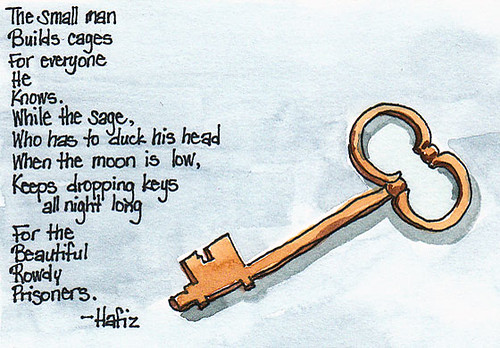

The moral, my friends, is to work hard and to keep an open mind so that you can take advantage of unexpected opportunities. But there’s another moral, and I think it’s just as important: Whenever possible, open doors for other people. The more chances we give others to succeed, the more likely they are to actually achieve success. Keep dropping keys all night long for the beautiful rowdy prisoners.